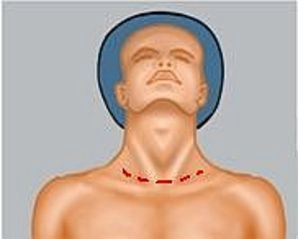

Collar incision in marked cutaneous emphysema

1.1 Position induced complications

In order to improve organ exposure in laparoscopic surgery, patients are often brought into extreme positions which may compromise long superficial nerves. Nerves particularly at risk include:

- Peroneal nerve

- Femoral nerve

- Ulnar nerve

- Brachial plexus

Prophylaxis

- Padded shoulder supports if Trendelenburg position is expected

- In lithotomy position the stirrups at the level of the head of the fibula should be padded with additional gel cushions

- When the arms are adducted, the elbow areas should be positioned on additional padding and loosely secured to the body pronated.

- Abducted arms should always be positioned on a padded support and never abducted beyond 90°

1.2 Trocar insertion complications

Insertion of the trocars and, particularly the first trocar, may injure hollow viscera and vessels; in many cases safe assessment and management of the injury will require speedy conversion to laparotomy. Laparoscopic assessment of retroperitoneal vascular injuries is almost impossible. Even if accidental intestinal injury could be managed laparoscopically, the possibility must be considered that there might be additional intra-abdominal injuries not evident at first glance.

1.3 Pneumoperitoneum-induced complications

Pneumoperitoneum may trigger a variety of pathologic changes in hemodynamics and the lungs, kidneys and endocrine organs. Depending on the intra-abdominal pressure, type of anesthesia, ventilation technique used, and the underlying disease, inadequate management of anesthesia may result in severe complications.

1.3.1 Cardiovascular complications

- Arrhythmia

- Cardiac arrest

- Pneumopericardium

- Hypotension/hypertension

1.3.2 Pulmonary complications

- Pulmonary edema

- Atelectases

- Air embolism

- Barotrauma

- Hypoxemia

- Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum

Emergency procedure

- Deflate the pneumoperitoneum

- If the anesthesiologist cannot manage the complication, consider conversion to open surgery or terminate the operation

Special case: Extreme subcutaneous emphysema

Up to 3% of all laparoscopies are complicated by collar skin emphysema; if left untreated it may threaten compression of the airways with secondary pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum and require CO2 deflation via a collar incision.As long as CO2 pneumothorax does not result in ventilation problems, watchful waiting is one possible option because the CO2 within the chest is rapidly absorbed. In case of ventilation problems or extensive pneumothorax a chest tube is indicated. Due to their flaccid tissue elderly patients are particularly at risk.

1.4. Organ specific complications

The complications specific to laparoscopic liver resection resemble those of open surgery. If they cannot be managed laparoscopically, conversion to laparotomy should not be delayed. Depending on the complication, proceed as described below:

1.4.1 Bleeding

Arterial bleeding

- May occur during dissection of the hepatic hilum but usually is easily managed

- Due to the risk of injury to bile duct structures and other vessels, bleeding in the hepatic hilum should not be blindly suture ligated, but better managed by successive dissection and specific measures under direct view.

- Arterial leakage: Direct suture with Prolene® 5-0 or 6-0 or clip

- In accidental transection of a major artery its reconstruction is mandatory, possibly reanastomose with a saphenous vein graft.

Venous bleeding

- e.g., from the portal vein, is much more difficult to manage: Under local control first attempt to gain overview, then clamp the vein close to its trunk and possibly suture it.

- Bleeding from the inferior vena cava is sometimes hard to control

- In retroperitoneal bleeding, which may spring up while freeing the liver, the inferior vena cava usually has not yet been freed enough to clamp it tangentially. In this case, the inferior vena cava must be grasped and compressed, best with forceps, after which the lesion is exposed and sutured; in this situation it is helpful if the inferior vena cava below the liver had been looped beforehand.

- When the inferior vena cava is bleeding at the level of its confluence with the hepatic veins, often the only management possible is by manual compression.

- In difficult situations it may become necessary to temporarily clamp the inferior vena cava cephalad and caudad of the liver. This may even require opening up the diaphragm at the caval foramen.

- Caution: There is the risk of air embolism!

Bleeding from the hepatic resection area

- Targeted suture ligation

- No deep bulk suture ligations because they result in necrosis of the surrounding parenchyma and may lead to injury of adjacent vessels, e.g. thin-walled hepatic veins.

- In diffuse bleeding: Coagulation, e.g., with an argon beamer

- Massive diffuse bleeding from the resection area (most often due to coagulopathy) may require temporary packing with towels.

Preventing intraoperative bleeding

- Adequate access with sufficient exposure

- Generous freeing of the liver

- Preliminary hilar ligatures in anatomical lobectomies

- Intraoperative ultrasonography with visualization of the vascular structures at the area of resection

- Controlled dissection of the parenchyma

- Avoiding venous system overload (low CVP)

- Careful management of the area of resection

Compromised arterial blood supply

- As a matter of principle, when dissecting the hilum care must be taken to prevent accidental injury to and ligature of the wrong artery. This would result in a significant complication.

1.4.2 Bile leakage

- With gallbladder present: Occlude the common bile duct and manually compress the gallbladder while simultaneously inspecting the resection area of the liver; possibly targeted suture ligation

- With the gallbladder already removed: Check with methylene blue or Lipovenös® (lipid emulsion) via the cystic stump: After methylene blue or Lipovenös® has been pressure injected into the bile duct system, bile leakage will be easily visible as discharge of blue solution /white lipid.

1.4.3 Air embolism

- Air embolism (in laparoscopic procedures: CO2 embolism) may occur through accidental or unnoticed openings in small hepatic veins; the symptoms include sudden tachycardia, hypotension, arterial hypoxemia, arrhythmia and elevated CVP. Low and even negative CVP encourages air embolism.

- Prevent further entry of air by detecting, clamping or suturing the point of entry, and immediately start PEEP ventilation.

1.4.4 Pneumothorax

- May occur in tumors close to or infiltrating the diaphragm → intraoperative chest tube

1.4.5 Transection of the common bile duct

- If after accidental transection of the common bile duct both stumps display good blood supply, they may be anastomosed directly, possibly T-tube drainage

- In case of possibly compromised blood supply hepaticojejunostomy is indicated

1.4.6 Injuries to hollow viscera

- Many patients with previous surgery, particularly after cholecystectomy or gastric procedures, require adhesiolysis. This may result in injury to hollow viscera.