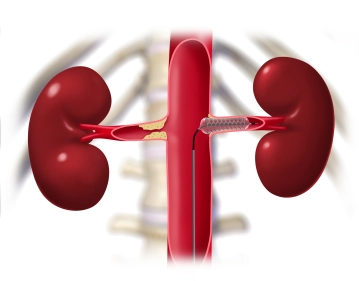

Because of the presumed ulcerated lumen of the stenosed renal arteries, avoid dissection and embolization from the outset by not predilating and deliver a 5 mm stent (length 20 mm).

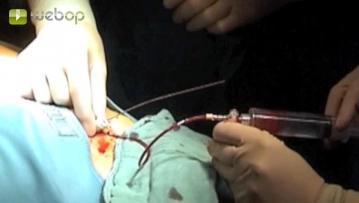

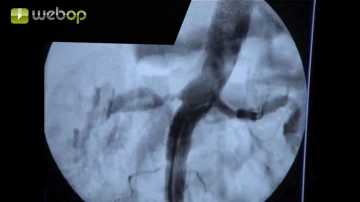

Advance the balloon-expandable stent through the RDC catheter and over the guidewire into the renal artery in roadmapping technique, and then carefully withdraw the RDC catheter. Deliver the stent with its central end approximately 1 mm outside the renal artery ostium in the aorta. Secure the guidewire and RDC catheter firmly to the patient's thigh to prevent dislodgement. Then deploy the stent by inflating the balloon.

Caution:

Do not inadvertently deploy the stent in the RDC catheter. This would create significant technical problems. In case of partial stent protrusion, there would even be the risk of dissection or perforation when retracting the guidewire.

Note:

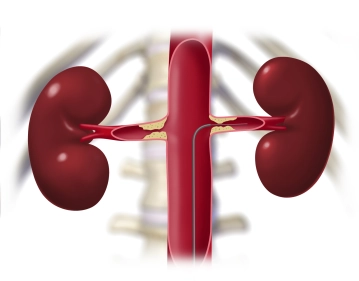

True renal artery stenosis at its aortic ostium is always caused by the calcified aortic wall. After balloon dilation, these stenoses always constrict like the iris diaphragm in a camera. Such stenoses always require stenting. Sometimes such stenoses are so hard that they must be predilated before stenting can be performed. Otherwise, the stent could not pass through the stenosis and might become damaged.

In most cases, stenosis directly downstream of the renal artery orifice is also very hard and the aorta likewise exhibits severe arteriosclerotic changes, as in the present case. Similarly, these stenoses quite often require stenting because the short-term postoperative outcome is poor.

RAS far from its ostium is mostly eccentric and easily dilated. This type of stenosis requires stenting only if there is significant residual stenosis following dilation.

Fibromuscular dysplasia of the renal arteries usually requires stenting because of their tendency to undergo restenosis due to the connective-tissue like scarring of the arterial wall with intimal ridges.