Pancreatic cancer currently constitutes the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Europe and is projected to rank second in cancer mortality by 2030.[1] The only potentially curative treatment option is surgical resection, which still barely results in a 5-year survival rate of just 10%.[2] Aggressive tumor biology in the past 10 years has culminated in the introduction of more effective new chemotherapeutic regimens, both adjuvant and neoadjuvant, establishing multimodal therapeutic approaches.

Indication for surgery

Initiated by the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV), evidence-based recommendations have been defined for the indication of surgery for pancreatic cancer, with the indication to be determined by a tumor board of experienced pancreatic surgeons in accordance with the guidelines and taking into account the specific characteristics of each patient.[3] These recommendations, which are based on the systematic analysis of 58 original papers and 10 guidelines, state that surgery is indicated in histologically confirmed pancreatic cancer as well as in highly suspected resectable pancreatic cancer.[3, 4]

Resectability

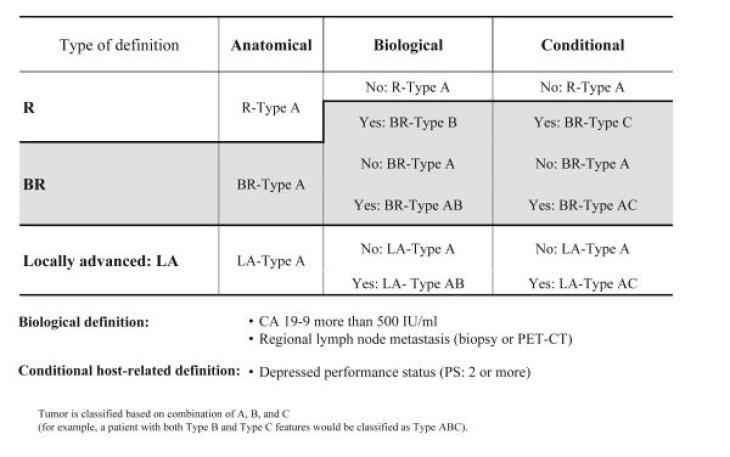

The greatest probability of survival is with margin-negative (R0) resection.[5, 6] The current guidelines now classify R0 as "R0 narrow" (≤┘1 mm) and "R0 wide" (>┘1 mm), when the carcinoma is less or more than one millimeter from the resection margin, respectively.[7] In addition to anatomic resectability (tumor location relative to major visceral vessels), since 2017 tumor biology and general status of the patient have been considered as co-decisive resectability criteria and included in the current S3 guidelines as the ABC consensus classification of resectability [8].

ABC criteria of resectability according to the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) consensus.

Source: Isaji S et al (2018) International consensus on definition and criteria of borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma 2017. Pancreatology18(1):2–11.

The S3 guidelines recommend contrast-enhanced 2-phase computed tomography imaging to assess anatomic resectability.[7] Based on the anatomic resectability criteria, tumors can be classified as primarily resectable, borderline resectable, and non-resectable or locally advanced.[7]

Assessment of biological resectability is most often based on the tumor marker CA 199. The cut-off value has been defined as >┘500 IU/mL, since above this threshold resectability is seen in less than 70% of cases and survival of less than 20 months can be expected. [8, 9]

ECOG performance status is also used as a conditional resectability criterion, where a patient status ≥ 2 herolds poor prognosis.[8]

Mesopancreas

The mesopancreas, the connective tissue region surrounding the large vessels of the pancreatic region, which is densely traversed by blood and lymphatic vessels as well as nerve plexuses, has been the subject of discussion for several years.[10] Meta-analyses suggest that total mesopancreatic resection yields oncologically superior outcomes.[11] Pancreatic head resection involves complete excision of the mesopancreatic tissue between the portal vein, hepatic artery, base of the celiac trunk, and superior mesenteric artery (triangle procedure [12, 13]), while radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy (RAMPS [14]) is performed in left-sided pancreatic resections ( cancer of the corpus, tail).

[RAMPS: Depending on the extent of the tumor, the RAMPS procedure is classified as anterior or posterior, in which the resection is essentially more radical posteriad. In anterior RAMPS, resection includes the Gerota fascia and perirenal fat on the left side. In contrast, posterior RAMPS involves resection of the left adrenal gland as well as Gerota fascia and perirenal fat.]

Vascular resection

Venous resections in high-volume centers increases morbidity and mortality only minimally and results in adequate overall survival.[15, 16] Thus, according to the current German S3 guidelines, the portal vein can be resected and revascularized in cases of tumor infiltration ≤┘180° or in complex situations such as cavernous transformation.[17] Arterial resections, on the other hand, are quite risky, often complex, and not infrequently require venous revascularization at the same time. Many patients do not benefit oncologically from these extensive procedures and quite often have poorer survival outcomes than patients without vascular resection.[18] Arterial resections should therefore be undertaken only in high volume centers.

Unexpected arterial resections can be avoided in pancreatic resection with curative intent by early exposure of the superior mesenteric artery and the celiac trunk to verify that they are free of tumor. The "artery-first" strategy helps avoid futile interventions, allows better planning of vascular resections and revascularizations, and improves long-term survival for selected patients in centers with appropriate expertise.[19]

Oligometastasis

The term oligometastasis first appeared in the current German S3 guidelines and denotes the presence of ≤┘3 metastases that should only be resected within trials as part of a multimodality treatment concept.[7] No randomized trials have been conducted to date, but resection of oligometastases appears to improve patient survival compared with palliative chemotherapy, particularly after neoadjuvant therapy.[20–23] In Germany, the HOLIPANC and METAPANC trials are currently addressing this issue.[24]

Neoadjuvant treatment concepts

For patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, the current German guidelines recommend preoperative chemotherapy or radiochemotherapy; in resectable cancer, it should not be performed outside of trials.[7] The recommendations are based on data from a meta-analysis and current published trial data.[25, 26] As it is difficult to assess resectability by image morphology after neoadjuvant treatment in initially borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancers, the guideline recommends surgical exploration in stable disease to assess secondary resectability.[7, 27] The decline in CA 199 level may also help in the assessment of secondary resectability.[28. 29]

Laparoscopic techniques and robotics in pancreatic cancer

Left-sided pancreatic resections and pancreatic head resections must be differentiated. For left-sided laparoscopic resections, the randomized-controlled LEOPARD trial demonstrated faster convalescence, less blood loss, and no higher complication rates compared with the open approach.[30] The data were confirmed by the combined analysis of the LEOPARD and LAPOPS trials.[31] However, the laparoscopic technique does not change the long-term quality of life.[32] A meta-analysis of prior data yielded similar rates for R0 resection and adjuvant chemotherapy.[33] At 28 and 31 months, median overall survival was the same for laparoscopic and open left-sided pancreatic resections, respectively.[34]

For pancreatic head resections, the LEOPARD-2 randomized controlled trial published in 2019 reported higher mortality (90-day mortality 10%) in the laparoscopic group, which lacked benefits over the open group in terms of postoperative pain, convalescence, inpatient length of stay, and quality of life.[36] A recent Chinese randomized trial found comparable mortality for laparoscopic pancreatic head resections with only a slight benefit favoring the laparoscopic technique.[37]

In the last 10 years, robot-assisted operations have also become established in pancreatic surgery. Thus, not only the technically less demanding left resection, but also the more complex pancreaticoduodenectomy is increasingly being performed with robot-assistance. However, this requires a long learning curve [37] and a definitive conclusion regarding oncologic outcomes is not yet possible. Only observational studies are available on the use of robot-assistance in malignant indications, demonstrating feasibility and offering potential benefits of the minimally invasive technique.[38, 39, 40] According to international guidelines, indication in malignancy is not a fundamental contraindication for robot-assistance, but the outcomes of randomized controlled trials, and thus high-quality results, are not expected for another 3 to 5 years.[41]

Centralization of pancreatic surgery

Postoperative mortality can be reduced and survival increased in high-volume pancreatic surgery centers.[42, 43, 44] Against this background, following a decision by the German Federal Joint Committe, the minimum case numbers required for billing complex pancreatic interventions will be increased from the current 10 to 20 resections per year starting in 2024.

Whipple procedure versus pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPD).

There are two surgical procedures available for resection of pancreatic head and periampullary cancer, the standard Kausch-Whipple procedure and the pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. The latter offers the benefit of preserving physiologic food passage and reducing dumping syndromes, postoperative weight loss, and gastroesophageal reflux.[45-52]

The more recent studies [49, 51, 52] demonstrated less need for blood transfusion and shorter length of inpatient stay in PPPD patients compared with the Whipple cohort. Both groups did not differ significantly in postoperative morbidity. The incidence of gastric emptying disorders was similar in both groups (Whipple 23% vs. PPPD 22%). Regarding radical surgery, no significant difference was observed either (R0 in Whipple 82.6% vs. 73.6% R0 in PPPD). Long-term follow-up revealed comparable overall survival rates.